Gastroenteritis: Razlika med redakcijama

(ni razlike)

|

Redakcija: 10:28, 1. marec 2015

Ta članek je za krajši čas rezerviran, saj ga namerava eden izmed sodelavcev v večji meri preurediti. Prosimo vas, da strani v tem času ne spreminjate, saj bi lahko prišlo do navzkrižja urejanj. Če je iz zgodovine strani razvidno, da je zadnjih nekaj dni ni spreminjal nihče, lahko to predlogo odstranite. |

| Gastroenteritis | |

|---|---|

| |

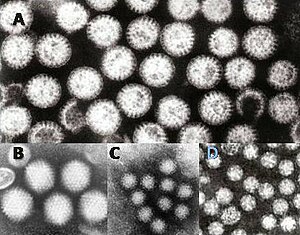

| Virusi gastroenteritisa: A = rotavirus, B = adenovirus, C = Norovirus in D = Astrovirus. Delce virusov so prikazani z isto povečavo, da je mogoče primerjati njih velikosti. | |

| Specialnost | gastroenterologija |

| Simptomi | bruhanje, driska, slabost, vročina, bolečina v trebuhu, zgaga, spazem, izsušitev, krči v trebuhu |

| Klasifikacija in zunanji viri | |

| MKB-10 | A02.0, A08, A09, J10.8, J11.8, K52 |

| MKB-9 | 008.8 009.0, 009.1, 558 |

| DiseasesDB | 30726 |

| MedlinePlus | 000252 000254 |

| eMedicine | emerg/213 |

| MeSH | D005759 |

Gastroenteritis ali nalezljiva driska je zdravstveno stanje zaradi vnetja ("-itis")v prebavil, v katerega sta vpletena želodec ("gastro" -) in tanko črevo ("Entero "-). Povzroča kombinacijo znakov, kot so driska, bruhanje ter bolečine in krči v trebuhu.[1] Kot posledica se lahko pojavi dehidracija. Gastroenteritisu pravijo po domače tudi gastro ali pa želodčni virus. Čeprav ni povezan z gripo, ga pogosto imenujejo trebušna gripa, ali pa želodčna gripa.

V svetovnem merilu večino primerov pri otrocih povzročajo rotavirusi.[2] Pri odraslih sta pogostejša norovirus[3] in Campylobacter[4] kot vzrok bolezni. Manj pogosti vzrokiso med drugim druge bakterije (ali njihovi strupi) in paraziti. Do prenosa lahko pride zaradi uživanja nepravilno pripravljenih živil ali onesnažene vode ali zaradi neposrednega stika z osebo, ki je kužna. Preprečuje se med drugim z rabo sveže vode, rednim umivanjem rok in z dojenjem, zlasti na območjih, kjer je sanitarne razmere niso zadovoljive. Cepivo proti rotavirusom se priporoča za vse otroke.

Ključno za zdravljenje je,za prizadeto osebo, da dobiva dovolj tekočine. Za lažje do zmerne primere je to običajno mogoče doseči s pomočjo peroralne raztopine za rehidracijo (t.j. kombinacije vode, soli in sladkorja). Pri prizadetih otrocih, ki se jih doji, je priporočljivo z dojenjem nadaljevati. V hujših primerih so lahko potrebne intravenozne tekočine v ambulanti. Antibiotiki na splošno niso priporočljivi. Gastroenteritis se predvsem loteva otrok in ljudi v razvijajočem se svetu. Letno gre za tri do pet milijard obolenj in 1.4 milijonov smrti.

Znaki in simptomi

Tipična znaka astroenteritisa sta driska in bruhanje,[5] manj pogosto le en ali drug znak.[1] Prisotni so lahko tudi krči trebuha.[1] Znaki in simptomi se običajno pojavijo 12-72 ur po okužbi s povzročiteljem.[6] Če gre za virusni izvor, bolezen običajno v enem tednu mine.[5] Nekatere oblike bolezni virusnega izvora se lahko tudi kažejo z vročino utrujenostjo, glavobolom in bolečimi mišicami.[5] Če gre za kri v blatu, so vzrok manj verjetno virusi[5] in bolj verjetno bakterije.[7] Nekatere oblike okužbe z bakterijami spremljajo hude bolečine v trebuhu, pri tem lahko trajajo tudi več tednov.[7]

Otroci, okuženi z rotavirusi, ponavadi popolnoma okrevajo v treh do osmih dneh.[8] V revnih državah pa za zdravljenje hudih okužb dostikrat ni možnosti, tako da je vztrajna driska pogosto prisotna. [9] Dehidracija je pogosten zaplet pri driski,[10] in otrok z visoko stopnjo dehidracije ima lahko podaljšano kapilarno polnjenje, slab turgor kože, in nenormalno dihanje.[11] Ponovne okužbe je običajno videti na območjih s slabim sanitarijami, posledica so podhranjenost,[6] zavrta rast in dolgoročne kognitivne kasnitve.[12]

Kot posledica okužb z vrsto Campylobacter se pri 1 % obolelih pojavi reaktivni artritis, pri 0,1 % pa sindrom Guillain-Barre.[7] Hemolitični uremični sindrom (HUS) je lahko posledica okužbe z bakterijami vrste Escherichia coli ali Shigella , ki tvorijo toksin Shiga toxin in povzročajo nizko število trombocitov, slabo delovanje ledvic in nizko število rdečih krvnih celic (zaradi njih razkroja).[13] Otroci so bolj kot odrasli ogroženi od HUS.[12] Nekatere virusne okužbe lahko povzročijo benigne infantilne napade.[1]

Vzrok

Virusi (zlasti rotavirus) in bakterije vrste Escherichia coli in Campylobacter so glavni vzroki za gastroenteritis.[6][14] Obstaja pa še veliko drugih kužnih agentov, ki lahko ta sindrom povzročijo.[12] Občasno je videti ne-kužne vzroke, ki pa so manj verjetni, kot pa virusi in bakterije.[1] Nevarnost okužbe je večja pri otrocih, zaradi njihove pomanjkljive imunitete in relativno slabe higiene.[1]

Virusi

Za rotavirus, norvirus, adenovirus, in [astrovirus]] se ve, da povzročajo virusni gastroenteritis.[5][15] Najpogostejši vzrok gastroenteritisa pri otrocih je rotavirus,[14] in pogostnosti obolenja v razvitem in nerazvitem svetu sta si podobni.[8] Virusi povzročajo približno 70% epizod nalezljive driske v pediatrični starostni skupini.[16] Rotavirus je zaradi pridobljene imunosti manj pogosto vzrok bolezni pri odraslih.[17] Norvirus je vzrok v približno 18 % vseh primerov.[18]

Norvirus je vodilni vzrok gastroenteritisa med odraslimi v Ameriki, kjer je vzrok za veö kot 90% izbruhov.[5] Do teh krajevno omejenih epidemij navadno pride, kadar je skupina ljudi prisiljena preživeti določen čas v tesnni fizični bližini, kot so to na primer potniške ladje,[5] bolnišnice ali restavracije.[1] Ljudje so lahko še dalje kužni tudi potem, ko je njih driske konec.[5] Norvirus je vzrok za približno 10 % primerov pri otrocih.[1]

Bakterije

Campylobacter jejuni je v razvitem svetu glavni vzrok za bakterijski gastroenteritis, polovica teh primerov zaradi izpostavljenosti perutnini.[7] Pri otrocih so bakterije so vzrok v približno 15 % primerov, pri čemer so najbolj pogoste vrste Escherichia coli , Salmonella , Shigella in Campylobacter.[16] Če je hrana kontaminirana z bakterijami in ostane nekaj ur pri sobni temperaturi, se bakterije razmnožje in pri osebah, ki hrano zaužijejo, se tveganje za okužbo ustrezno poveča. [12] Nekatera živila, pogosto povezana z boleznijo, so med drugim surovo ali kuhano meso, perutnina, morski sadeži in jajca; surovi kalčki; nepasterizirano mleko in mehki siri; ter sadni in zelenjavni sokovi.[19] V državah v razvoju, še posebej v podsaharski Afriki in Aziji, je kolera pogosto vzrok za gastroenteritis. Ta okužba se običajno prenaša s kontaminirano vodo ali hrano.[20]

Strupe proizvajajoča Clostridium difficile , je pomemben vzrok za drisko, ki se pogosteje pojavlja pri starejših.[12] Otroci lahko nosijo te bakterije brez pojava simptomov.[12] Je pogosten vzrok za drisko pri osebah, ki so sprejete v bolnišnico, pogosto se navezuje na uporabo antibiotikov.[21] Staphylococcus aureus kot povzročitelj kužne drisske se lahko pojavijo tudi pri ljudeh, ki so jemali antibiotike.[22] "Driska na poti" je ponavadi ena od bakterijskih oblik gastroenteritisa. Zdravila, ki zbijajo kislino, zgleda povečujejo tveganje za občutne okužbe ob izpostavljenosti številnim organizmom, med drugim Clostridium difficile, Salmonelli' in Campylobacter.[23] Tveganje je pri jemanju zaviralcev protonske črpalke večje kot pri H2 antagonisti h.[23]

Paraziti

Številne praživali lahko povzročijo gastroenteritis - najpogosteje Giardia lamblia - pa tudi Entamoeba histolytica in Cryptosporidium sta že bili vpleteni.[16] Kot skupina so ti agenti krivi za okoli 10 % primerov pri otrocih.[13] Giardia se pojavlja pogosteje v državah v razvoju, vendar je ta povzročitelj bolezni do neke mere prisoten skoraj povsod.[24] Pojavlja se pogosteje pri osebah, ki se vračajo z območij z visoko prevalenco, pri otrokih, ki obiskujejo dnevno varstvo, pri moških, ki imajo spolne odnose z moškimi, in po nesrečah.[24]

Prenos

Transmission may occur via consumption of contaminated water, or when people share personal objects.[6] In places with wet and dry seasons, water quality typically worsens during the wet season, and this correlates with the time of outbreaks.[6] In areas of the world with four seasons, infections are more common in the winter.[12] Bottle-feeding of babies with improperly sanitized bottles is a significant cause on a global scale.[6] Transmission rates are also related to poor hygiene, especially among children,[5] in crowded households,[25] and in those with pre-existing poor nutritional status.[12] After developing tolerance, adults may carry certain organisms without exhibiting signs or symptoms, and thus act as natural reservoirs of contagion.[12] While some agents (such as Shigella) only occur in primates, others may occur in a wide variety of animals (such as Giardia).[12]

Non-infectious

There are a number of non-infectious causes of inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract.[1] Some of the more common include medications (like NSAIDs), certain foods such as lactose (in those who are intolerant), and gluten (in those with celiac disease). Crohn's disease is also a non-infection source of (often severe) gastroenteritis.[1] Disease secondary to toxins may also occur. Some food related conditions associated with nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea include: ciguatera poisoning due to consumption of contaminated predatory fish, scombroid associated with the consumption of certain types of spoiled fish, tetrodotoxin poisoning from the consumption of puffer fish among others, and botulism typically due to improperly preserved food.[26]

In the United States, rates of emergency department use for noninfectious gastroenteritis dropped 30% from 2006 until 2011. Of the twenty most common conditions seen in the ED, rates of noninfectious gastroenteritis had the largest decrease in visits in that time period.[27]

Patofiziologija

Gastroenteritis is defined as vomiting or diarrhea due to infection of the small or large bowel.[12] Spremembe v tankem črevesu, so običajno ne-vnetnega znaöaja, na debelem črevesu pa gre za vnetne spremembe.[12] The number of pathogens required to cause an infection varies from as few as one (for Cryptosporidium) to as many as 108 (for Vibrio cholerae).[12]

Diagnoza

Gastroenteritis is typically diagnosed clinically, based on a person's signs and symptoms.[5] Determining the exact cause is usually not needed as it does not alter management of the condition.[6] However, stool cultures should be performed in those with blood in the stool, those who might have been exposed to food poisoning, and those who have recently traveled to the developing world.[16] Diagnostic testing may also be done for surveillance.[5] As hypoglycemia occurs in approximately 10% of infants and young children, measuring serum glucose in this population is recommended.[11] Electrolytes and kidney function should also be checked when there is a concern about severe dehydration.[16]

Dehydration

A determination of whether or not the person has dehydration is an important part of the assessment, with dehydration typically divided into mild (3–5%), moderate (6–9%), and severe (≥10%) cases.[1] In children, the most accurate signs of moderate or severe dehydration are a prolonged capillary refill, poor skin turgor, and abnormal breathing.[11][28] Other useful findings (when used in combination) include sunken eyes, decreased activity, a lack of tears, and a dry mouth.[1] A normal urinary output and oral fluid intake is reassuring.[11] Laboratory testing is of little clinical benefit in determining the degree of dehydration.[1]

Diferencialna diagnoza

Other potential causes of signs and symptoms that mimic those seen in gastroenteritis that need to be ruled out include appendicitis, volvulus, inflammatory bowel disease, urinary tract infections, and diabetes mellitus.[16] Pancreatic insufficiency, short bowel syndrome, Whipple's disease, coeliac disease, and laxative abuse should also be considered.[29] The differential diagnosis can be complicated somewhat if the person exhibits only vomiting or diarrhea (rather than both).[1]

Appendicitis may present with vomiting, abdominal pain, and a small amount of diarrhea in up to 33% of cases.[1] This is in contrast to the large amount of diarrhea that is typical of gastroenteritis.[1] Infections of the lungs or urinary tract in children may also cause vomiting or diarrhea.[1] Classical diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) presents with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting, but without diarrhea.[1] One study found that 17% of children with DKA were initially diagnosed as having gastroenteritis.[1]

Preventiva

Življenjski slog

A supply of easily accessible uncontaminated water and good sanitation practices are important for reducing rates of infection and clinically significant gastroenteritis.[12] Personal measures (such as hand washing with soap) have been found to decrease incidence and prevalence rates of gastroenteritis in both the developing and developed world by as much as 30%.[11] Alcohol-based gels may also be effective.[11] Breastfeeding is important, especially in places with poor hygiene, as is improvement of hygiene generally.[6] Breast milk reduces both the frequency of infections and their duration.[1] Avoiding contaminated food or drink should also be effective.[30]

Vaccination

Due to both its effectiveness and safety, in 2009 the World Health Organization recommended that the rotavirus vaccine be offered to all children globally.[14][31] Two commercial rotavirus vaccines exist and several more are in development.[31] In Africa and Asia these vaccines reduced severe disease among infants[31] and countries that have put in place national immunization programs have seen a decline in the rates and severity of disease.[32][33] This vaccine may also prevent illness in non-vaccinated children by reducing the number of circulating infections.[34] Since 2000, the implementation of a rotavirus vaccination program in the United States has substantially decreased the number of cases of diarrhea by as much as 80 percent.[35][36][37] The first dose of vaccine should be given to infants between 6 and 15 weeks of age.[14] The oral cholera vaccine has been found to be 50–60% effective over 2 years.[38]

Obvladovanje

Gastroenteritis is usually an acute and self-limiting disease that does not require medication.[10] The preferred treatment in those with mild to moderate dehydration is oral rehydration therapy (ORT).[13] Metoclopramide and/or ondansetron, however, may be helpful in some children,[39] and butylscopolamine is useful in treating abdominal pain.[40]

Rehydration

The primary treatment of gastroenteritis in both children and adults is rehydration. This is preferably achieved by oral rehydration therapy, although intravenous delivery may be required if there is a decreased level of consciousness or if dehydration is severe.[41][42] Oral replacement therapy products made with complex carbohydrates (i.e. those made from wheat or rice) may be superior to those based on simple sugars.[43] Drinks especially high in simple sugars, such as soft drinks and fruit juices, are not recommended in children under 5 years of age as they may increase diarrhea.[10] Plain water may be used if more specific and effective ORT preparations are unavailable or are not palatable.[10] A nasogastric tube can be used in young children to administer fluids if warranted.[16]

Dietary

It is recommended that breast-fed infants continue to be nursed in the usual fashion, and that formula-fed infants continue their formula immediately after rehydration with ORT.[44] Lactose-free or lactose-reduced formulas usually are not necessary.[44] Children should continue their usual diet during episodes of diarrhea with the exception that foods high in simple sugars should be avoided.[44] The BRAT diet (bananas, rice, applesauce, toast and tea) is no longer recommended, as it contains insufficient nutrients and has no benefit over normal feeding.[44] Some probiotics have been shown to be beneficial in reducing both the duration of illness and the frequency of stools.[45][46] They may also be useful in preventing and treating antibiotic associated diarrhea.[47] Fermented milk products (such as yogurt) are similarly beneficial.[48] Zinc supplementation appears to be effective in both treating and preventing diarrhea among children in the developing world.[49]

Antiemetics

Antiemetic medications may be helpful for treating vomiting in children. Ondansetron has some utility, with a single dose being associated with less need for intravenous fluids, fewer hospitalizations, and decreased vomiting.[50][51][52] Metoclopramide might also be helpful.[52] However, the use of ondansetron might possibly be linked to an increased rate of return to hospital in children.[53] The intravenous preparation of ondansetron may be given orally if clinical judgment warrants.[54] Dimenhydrinate, while reducing vomiting, does not appear to have a significant clinical benefit.[1]

Antibiotiki

Antibiotics are not usually used for gastroenteritis, although they are sometimes recommended if symptoms are particularly severe[55] or if a susceptible bacterial cause is isolated or suspected.[56] If antibiotics are to be employed, a macrolide (such as azithromycin) is preferred over a fluoroquinolone due to higher rates of resistance to the latter.[7] Pseudomembranous colitis, usually caused by antibiotic use, is managed by discontinuing the causative agent and treating it with either metronidazole or vancomycin.[57] Bacteria and protozoans that are amenable to treatment include Shigella[58] Salmonella typhi,[59] and Giardia species.[24] In those with Giardia species or Entamoeba histolytica, tinidazole treatment is recommended and superior to metronidazole.[24][60] The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the use of antibiotics in young children who have both bloody diarrhea and fever.[1]

Antimotility agents

Antimotility medication has a theoretical risk of causing complications, and although clinical experience has shown this to be unlikely,[29] these drugs are discouraged in people with bloody diarrhea or diarrhea that is complicated by fever.[61] Loperamide, an opioid analogue, is commonly used for the symptomatic treatment of diarrhea.[62] Loperamide is not recommended in children, however, as it may cross the immature blood–brain barrier and cause toxicity. Bismuth subsalicylate, an insoluble complex of trivalent bismuth and salicylate, can be used in mild to moderate cases,[29] but salicylate toxicity is theoretically possible.[1]

Epidemiologija

no data ≤less 500 500–1000 1000–1500 1500–2000 2000–2500 2500–3000 | 3000–3500 3500–4000 4000–4500 4500–5000 5000–6000 ≥6000 |

It is estimated that three to five billion cases of gastroenteritis resulting in 1.4 million deaths occur globally on an annual basis,[13][63] with children and those in the developing world being primarily affected.[6] As of 2011, in those less than five, there were about 1.7 billion cases resulting in 0.7 million deaths,[64] with most of these occurring in the world's poorest nations.[12] More than 450,000 of these fatalities are due to rotavirus in children under 5 years of age.[65][66] Cholera causes about three to five million cases of disease and kills approximately 100,000 people yearly.[20] In the developing world children less than two years of age frequently get six or more infections a year that result in clinically significant gastroenteritis.[12] It is less common in adults, partly due to the development of acquired immunity.[5]

In 1980, gastroenteritis from all causes caused 4.6 million deaths in children, with the majority occurring in the developing world.[57] Death rates were reduced significantly (to approximately 1.5 million deaths annually) by the year 2000, largely due to the introduction and widespread use of oral rehydration therapy.[67] In the US, infections causing gastroenteritis are the second most common infection (after the common cold), and they result in between 200 and 375 million cases of acute diarrhea[5][12] and approximately ten thousand deaths annually,[12] with 150 to 300 of these deaths in children less than five years of age.[1]

Zgodovina

The first usage of "gastroenteritis" was in 1825.[68] Before this time it was more specifically known as typhoid fever or "cholera morbus", among others, or less specifically as "griping of the guts", "surfeit", "flux", "colic", "bowel complaint", or any one of a number of other archaic names for acute diarrhea.[69]

Družba in kultura

Gastroenteritis is associated with many colloquial names, including "Montezuma's revenge", "Delhi belly", "la turista", and "back door sprint", among others.[12] It has played a role in many military campaigns and is believed to be the origin of the term "no guts no glory".[12]

Gastroenteritis is the main reason for 3.7 million visits to physicians a year in the United States[1] and 3 million visits in France.[70] In the United States gastroenteritis as a whole is believed to result in costs of 23 billion USD per year[71] with that due to rotavirus alone resulting in estimated costs of 1 billion USD a year.[1]

Raziskave

There are a number of vaccines against gastroenteritis in development. For example, vaccines against Shigella and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC), two of the leading bacterial causes of gastroenteritis worldwide.[72][73]

Druge živali

Many of the same agents cause gastroenteritis in cats and dogs as in humans. The most common organisms are Campylobacter, Clostridium difficile, Clostridium perfringens, and Salmonella.[74] A large number of toxic plants may also cause symptoms.[75]

Some agents are more specific to a certain species. Transmissible gastroenteritis coronavirus (TGEV) occurs in pigs resulting in vomiting, diarrhea, and dehydration.[76] It is believed to be introduced to pigs by wild birds and there is no specific treatment available.[77] It is not transmissible to humans.[78]

Sklici

- ↑ 1,00 1,01 1,02 1,03 1,04 1,05 1,06 1,07 1,08 1,09 1,10 1,11 1,12 1,13 1,14 1,15 1,16 1,17 1,18 1,19 1,20 1,21 1,22 1,23 1,24 1,25 Singh, Amandeep (Julij 2010). »Pediatric Emergency Medicine Practice Acute Gastroenteritis — An Update«. Emergency Medicine Practice. 7 (7).

- ↑ Tate JE, Burton AH, Boschi-Pinto C, Steele AD, Duque J, Parashar UD (Februar 2012). »2008 estimate of worldwide rotavirus-associated mortality in children younger than 5 years before the introduction of universal rotavirus vaccination programmes: a systematic review and meta-analysis«. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 12 (2): 136–41. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70253-5. PMID 22030330.

{{navedi časopis}}: Vzdrževanje CS1: več imen: seznam avtorjev (povezava) - ↑ Marshall JA, Bruggink LD (april 2011). »The dynamics of norovirus outbreak epidemics: recent insights«. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 8 (4): 1141–9. doi:10.3390/ijerph8041141. PMC 3118882. PMID 21695033.

{{navedi časopis}}: Vzdrževanje CS1: samodejni prevod datuma (povezava) - ↑ Man SM (december 2011). »The clinical importance of emerging Campylobacter species«. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 8 (12): 669–85. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2011.191. PMID 22025030.

{{navedi časopis}}: Vzdrževanje CS1: samodejni prevod datuma (povezava) - ↑ 5,00 5,01 5,02 5,03 5,04 5,05 5,06 5,07 5,08 5,09 5,10 5,11 5,12 Eckardt AJ, Baumgart DC (Januar 2011). »Viral gastroenteritis in adults«. Recent Patents on Anti-infective Drug Discovery. 6 (1): 54–63. doi:10.2174/157489111794407877. PMID 21210762.

- ↑ 6,0 6,1 6,2 6,3 6,4 6,5 6,6 6,7 6,8 Webber, Roger (2009). Communicable disease epidemiology and control : a global perspective (3rd izd.). Wallingford, Oxfordshire: Cabi. str. 79. ISBN 978-1-84593-504-7.

- ↑ 7,0 7,1 7,2 7,3 7,4 Galanis, E (11. september 2007). »Campylobacter and bacterial gastroenteritis«. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association. 177 (6): 570–1. doi:10.1503/cmaj.070660. PMC 1963361. PMID 17846438.

- ↑ 8,0 8,1 Meloni, A; Locci, D; Frau, G; Masia, G; Nurchi, AM; Coppola, RC (Oktober 2011). »Epidemiology and prevention of rotavirus infection: an underestimated issue?«. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstetricians. 24 (Suppl 2): 48–51. doi:10.3109/14767058.2011.601920. PMID 21749188.

- ↑ »Toolkit«. DefeatDD. Pridobljeno 3. maja 2012.

- ↑ 10,0 10,1 10,2 10,3 »Management of acute diarrhoea and vomiting due to gastoenteritis in children under 5«. National Institute of Clinical Excellence. april 2009.

{{navedi splet}}: Vzdrževanje CS1: samodejni prevod datuma (povezava) - ↑ 11,0 11,1 11,2 11,3 11,4 11,5 Tintinalli, Judith E. (2010). Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide (Emergency Medicine (Tintinalli)). New York: McGraw-Hill Companies. str. 830–839. ISBN 0-07-148480-9.

- ↑ 12,00 12,01 12,02 12,03 12,04 12,05 12,06 12,07 12,08 12,09 12,10 12,11 12,12 12,13 12,14 12,15 12,16 12,17 12,18 12,19 Mandell 2010, Ch. 93

- ↑ 13,0 13,1 13,2 13,3 Elliott, EJ (6. januar 2007). »Acute gastroenteritis in children«. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 334 (7583): 35–40. doi:10.1136/bmj.39036.406169.80. PMC 1764079. PMID 17204802.

- ↑ 14,0 14,1 14,2 14,3 Szajewska, H; Dziechciarz, P (Januar 2010). »Gastrointestinal infections in the pediatric population«. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology. 26 (1): 36–44. doi:10.1097/MOG.0b013e328333d799. PMID 19887936.

- ↑ Dennehy PH (Januar 2011). »Viral gastroenteritis in children«. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 30 (1): 63–4. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3182059102. PMID 21173676.

- ↑ 16,0 16,1 16,2 16,3 16,4 16,5 16,6 Webb, A; Starr, M (april 2005). »Acute gastroenteritis in children«. Australian family physician. 34 (4): 227–31. PMID 15861741.

{{navedi časopis}}: Vzdrževanje CS1: samodejni prevod datuma (povezava) - ↑ Desselberger U, Huppertz HI (Januar 2011). »Immune responses to rotavirus infection and vaccination and associated correlates of protection«. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 203 (2): 188–95. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiq031. PMC 3071058. PMID 21288818.

- ↑ Ahmed, Sharia M; Hall, Aron J; Robinson, Anne E; Verhoef, Linda; Premkumar, Prasanna; Parashar, Umesh D; Koopmans, Marion; Lopman, Benjamin A (Avgust 2014). »Global prevalence of norovirus in cases of gastroenteritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis«. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 14 (8): 725–30. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70767-4. PMID 24981041.

- ↑ Nyachuba, DG (Maj 2010). »Foodborne illness: is it on the rise?«. Nutrition Reviews. 68 (5): 257–69. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00286.x. PMID 20500787.

- ↑ 20,0 20,1 Charles, RC; Ryan, ET (Oktober 2011). »Cholera in the 21st century«. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 24 (5): 472–7. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e32834a88af. PMID 21799407.

- ↑ Moudgal, V; Sobel, JD (Februar 2012). »Clostridium difficile colitis: a review«. Hospital practice (1995). 40 (1): 139–48. doi:10.3810/hp.2012.02.954. PMID 22406889.

- ↑ Lin, Z; Kotler, DP; Schlievert, PM; Sordillo, EM (Maj 2010). »Staphylococcal enterocolitis: forgotten but not gone?«. Digestive diseases and sciences. 55 (5): 1200–7. doi:10.1007/s10620-009-0886-1. PMID 19609675.

- ↑ 23,0 23,1 Leonard, J (september 2007). »Systematic review of the risk of enteric infection in patients taking acid suppression«. The American journal of gastroenterology. 102 (9): 2047–56, quiz 2057. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01275.x. PMID 17509031.

{{navedi časopis}}: Prezrt neznani parameter|coauthors=(predlagano je|author=) (pomoč)Vzdrževanje CS1: samodejni prevod datuma (povezava) - ↑ 24,0 24,1 24,2 24,3 Escobedo, AA; Almirall, P; Robertson, LJ; Franco, RM; Hanevik, K; Mørch, K; Cimerman, S (Oktober 2010). »Giardiasis: the ever-present threat of a neglected disease«. Infectious disorders drug targets. 10 (5): 329–48. doi:10.2174/187152610793180821. PMID 20701575.

- ↑ Grimwood, K; Forbes, DA (december 2009). »Acute and persistent diarrhea«. Pediatric clinics of North America. 56 (6): 1343–61. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2009.09.004. PMID 19962025.

{{navedi časopis}}: Vzdrževanje CS1: samodejni prevod datuma (povezava) - ↑ Lawrence, DT; Dobmeier, SG; Bechtel, LK; Holstege, CP (Maj 2007). »Food poisoning«. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 25 (2): 357–73, abstract ix. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2007.02.014. PMID 17482025.

- ↑ Skiner HG, Blanchard J, Elixhauser A (september 2014). »Trends in Emergency Department Visits, 2006-2011«. HCUP Statistical Brief #179. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

{{navedi splet}}: Vzdrževanje CS1: samodejni prevod datuma (povezava) Vzdrževanje CS1: več imen: seznam avtorjev (povezava) - ↑ Steiner, MJ (9. junij 2004). »Is this child dehydrated?«. JAMA : the Journal of the American Medical Association. 291 (22): 2746–54. doi:10.1001/jama.291.22.2746. PMID 15187057.

{{navedi časopis}}: Prezrt neznani parameter|coauthors=(predlagano je|author=) (pomoč) - ↑ 29,0 29,1 29,2 Warrell D.A., Cox T.M., Firth J.D., Benz E.J., ur. (2003). The Oxford Textbook of Medicine (4th izd.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-262922-0.

{{navedi knjigo}}: Vzdrževanje CS1: več imen: seznam urednikov (povezava) - ↑ »Viral Gastroenteritis«. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Februar 2011. Pridobljeno 16. aprila 2012.

- ↑ 31,0 31,1 31,2 World Health Organization (december 2009). »Rotavirus vaccines: an update« (PDF). Weekly epidemiological record. 51–52 (84): 533–540. PMID 20034143. Pridobljeno 10. maja 2012.

{{navedi časopis}}: Vzdrževanje CS1: samodejni prevod datuma (povezava) - ↑ Giaquinto, C (Julij 2011). »Summary of effectiveness and impact of rotavirus vaccination with the oral pentavalent rotavirus vaccine: a systematic review of the experience in industrialized countries«. Human Vaccines. 7 (7): 734–748. doi:10.4161/hv.7.7.15511. PMID 21734466. Pridobljeno 10. maja 2012.

{{navedi časopis}}: Prezrt neznani parameter|coauthors=(predlagano je|author=) (pomoč) - ↑ Jiang, V; Jiang B; Tate J; Parashar UD; Patel MM (Julij 2010). »Performance of rotavirus vaccines in developed and developing countries«. Human Vaccines. 6 (7): 532–542. doi:10.4161/hv.6.7.11278. PMC 3322519. PMID 20622508. Pridobljeno 10. maja 2012.

- ↑ Patel, MM; Steele, D; Gentsch, JR; Wecker, J; Glass, RI; Parashar, UD (Januar 2011). »Real-world impact of rotavirus vaccination«. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 30 (1 Suppl): S1–5. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3181fefa1f. PMID 21183833.

- ↑ US Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2008). »Delayed onset and diminished magnitude of rotavirus activity—United States, November 2007–May 2008«. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 57 (25): 697–700. PMID 18583958. Pridobljeno 3. maja 2012.

- ↑ »Reduction in rotavirus after vaccine introduction—United States, 2000–2009«. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 58 (41): 1146–9. Oktober 2009. PMID 19847149.

- ↑ Tate, JE (Januar 2011). »Uptake, impact, and effectiveness of rotavirus vaccination in the United States: review of the first 3 years of postlicensure data«. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 30 (1 Suppl): S56–60. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3181fefdc0. PMID 21183842.

{{navedi časopis}}: Prezrt neznani parameter|coauthors=(predlagano je|author=) (pomoč) - ↑ Sinclair, D; Abba, K; Zaman, K; Qadri, F; Graves, PM (16. marec 2011). Sinclair, David (ur.). »Oral vaccines for preventing cholera«. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD008603. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008603.pub2. PMID 21412922.

- ↑ Alhashimi D, Al-Hashimi H, Fedorowicz Z (2009). Alhashimi, Dunia (ur.). »Antiemetics for reducing vomiting related to acute gastroenteritis in children and adolescents«. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD005506. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005506.pub4. PMID 19370620.

{{navedi časopis}}: Vzdrževanje CS1: več imen: seznam avtorjev (povezava) - ↑ Tytgat GN (2007). »Hyoscine butylbromide: a review of its use in the treatment of abdominal cramping and pain«. Drugs. 67 (9): 1343–57. doi:10.2165/00003495-200767090-00007. PMID 17547475.

- ↑ »BestBets: Fluid Treatment of Gastroenteritis in Adults«.

- ↑ Canavan A, Arant BS (Oktober 2009). »Diagnosis and management of dehydration in children«. Am Fam Physician. 80 (7): 692–6. PMID 19817339.

- ↑ Gregorio GV, Gonzales ML, Dans LF, Martinez EG (2009). Gregorio, Germana V (ur.). »Polymer-based oral rehydration solution for treating acute watery diarrhoea«. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD006519. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006519.pub2. PMID 19370638.

{{navedi časopis}}: Vzdrževanje CS1: več imen: seznam avtorjev (povezava) - ↑ 44,0 44,1 44,2 44,3 King CK, Glass R, Bresee JS, Duggan C (november 2003). »Managing acute gastroenteritis among children: oral rehydration, maintenance, and nutritional therapy«. MMWR Recomm Rep. 52 (RR-16): 1–16. PMID 14627948.

{{navedi časopis}}: Vzdrževanje CS1: samodejni prevod datuma (povezava) Vzdrževanje CS1: več imen: seznam avtorjev (povezava) - ↑ Allen SJ, Martinez EG, Gregorio GV, Dans LF (2010). Allen, Stephen J (ur.). »Probiotics for treating acute infectious diarrhoea«. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 11 (11): CD003048. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003048.pub3. PMID 21069673.

{{navedi časopis}}: Vzdrževanje CS1: več imen: seznam avtorjev (povezava) - ↑ Feizizadeh, S; Salehi-Abargouei, A; Akbari, V (Julij 2014). »Efficacy and safety of Saccharomyces boulardii for acute diarrhea«. Pediatrics. 134 (1): e176-91. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-3950. PMID 24958586.

- ↑ Hempel, S; Newberry, SJ; Maher, AR; Wang, Z; Miles, JN; Shanman, R; Johnsen, B; Shekelle, PG (9. maj 2012). »Probiotics for the prevention and treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis«. JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 307 (18): 1959–69. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.3507. PMID 22570464.

- ↑ Mackway-Jones, Kevin (Junij 2007). »Does yogurt decrease acute diarrhoeal symptoms in children with acute gastroenteritis?«. BestBets.

- ↑ Telmesani, AM (Maj 2010). »Oral rehydration salts, zinc supplement and rota virus vaccine in the management of childhood acute diarrhea«. Journal of family and community medicine. 17 (2): 79–82. doi:10.4103/1319-1683.71988. PMC 3045093. PMID 21359029.

- ↑ DeCamp LR, Byerley JS, Doshi N, Steiner MJ (september 2008). »Use of antiemetic agents in acute gastroenteritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis«. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 162 (9): 858–65. doi:10.1001/archpedi.162.9.858. PMID 18762604.

{{navedi časopis}}: Vzdrževanje CS1: samodejni prevod datuma (povezava) Vzdrževanje CS1: več imen: seznam avtorjev (povezava) - ↑ Mehta S, Goldman RD (2006). »Ondansetron for acute gastroenteritis in children«. Can Fam Physician. 52 (11): 1397–8. PMC 1783696. PMID 17279195.

- ↑ 52,0 52,1 Fedorowicz, Z (7. september 2011). Fedorowicz, Zbys (ur.). »Antiemetics for reducing vomiting related to acute gastroenteritis in children and adolescents«. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9 (9): CD005506. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005506.pub5. PMID 21901699.

{{navedi časopis}}: Prezrt neznani parameter|coauthors=(predlagano je|author=) (pomoč) - ↑ Sturm JJ, Hirsh DA, Schweickert A, Massey R, Simon HK (Maj 2010). »Ondansetron use in the pediatric emergency department and effects on hospitalization and return rates: are we masking alternative diagnoses?«. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 55 (5): 415–22. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.11.011. PMID 20031265.

{{navedi časopis}}: Vzdrževanje CS1: več imen: seznam avtorjev (povezava) - ↑ »Ondansetron«. Lexi-Comp. Maj 2011.

- ↑ Traa BS, Walker CL, Munos M, Black RE (april 2010). »Antibiotics for the treatment of dysentery in children«. Int J Epidemiol. 39 (Suppl 1): i70–4. doi:10.1093/ije/dyq024. PMC 2845863. PMID 20348130.

{{navedi časopis}}: Vzdrževanje CS1: samodejni prevod datuma (povezava) Vzdrževanje CS1: več imen: seznam avtorjev (povezava) - ↑ Grimwood K, Forbes DA (december 2009). »Acute and persistent diarrhea«. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 56 (6): 1343–61. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2009.09.004. PMID 19962025.

{{navedi časopis}}: Vzdrževanje CS1: samodejni prevod datuma (povezava) - ↑ 57,0 57,1 Mandell, Gerald L.; Bennett, John E.; Dolin, Raphael (2004). Mandell's Principles and Practices of Infection Diseases (6th izd.). Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 0-443-06643-4.

- ↑ Christopher, PR (4. avgust 2010). Christopher, Prince RH (ur.). »Antibiotic therapy for Shigella dysentery«. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (8): CD006784. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006784.pub4. PMID 20687081.

{{navedi časopis}}: Prezrt neznani parameter|coauthors=(predlagano je|author=) (pomoč) - ↑ Effa, EE (5. oktober 2011). Bhutta, Zulfiqar A (ur.). »Fluoroquinolones for treating typhoid and paratyphoid fever (enteric fever)«. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (10): CD004530. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004530.pub4. PMID 21975746.

{{navedi časopis}}: Prezrt neznani parameter|coauthors=(predlagano je|author=) (pomoč) - ↑ Gonzales, ML (15. april 2009). Gonzales, Maria Liza M (ur.). »Antiamoebic drugs for treating amoebic colitis«. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD006085. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006085.pub2. PMID 19370624.

{{navedi časopis}}: Prezrt neznani parameter|coauthors=(predlagano je|author=) (pomoč) - ↑ Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (16th izd.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-140235-7.

- ↑ Feldman, Mark; Friedman, Lawrence S.; Sleisenger, Marvin H. (2002). Sleisenger & Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease (7th izd.). Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-8973-6.

- ↑ Lozano, R (15. december 2012). »Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010«. Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. PMID 23245604.

- ↑ Walker, CL; Rudan, I; Liu, L; Nair, H; Theodoratou, E; Bhutta, ZA; O'Brien, KL; Campbell, H; Black, RE (20. april 2013). »Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea«. Lancet. 381 (9875): 1405–16. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60222-6. PMID 23582727.

- ↑ Tate, JE (Februar 2012). »2008 estimate of worldwide rotavirus-associated mortality in children younger than 5 years before the introduction of universal rotavirus vaccination programmes: a systematic review and meta-analysis«. The Lancet infectious diseases. 12 (2): 136–41. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70253-5. PMID 22030330.

{{navedi časopis}}: Prezrt neznani parameter|coauthors=(predlagano je|author=) (pomoč) - ↑ World Health Organization (november 2008). »Global networks for surveillance of rotavirus gastroenteritis, 2001–2008« (PDF). Weekly Epidemiological Record. 47 (83): 421–428. PMID 19024780. Pridobljeno 10. maja 2012.

{{navedi časopis}}: Vzdrževanje CS1: samodejni prevod datuma (povezava) - ↑ Victora CG, Bryce J, Fontaine O, Monasch R (2000). »Reducing deaths from diarrhoea through oral rehydration therapy«. Bull. World Health Organ. 78 (10): 1246–55. PMC 2560623. PMID 11100619.

{{navedi časopis}}: Vzdrževanje CS1: več imen: seznam avtorjev (povezava) - ↑ »Gastroenteritis«. Oxford English Dictionary 2011. Pridobljeno 15. januarja 2012.

- ↑ Rudy's List of Archaic Medical Terms

- ↑ Flahault, A; Hanslik, T (november 2010). »[Epidemiology of viral gastroenteritis in France and Europe]«. Bulletin de l'Academie nationale de medecine. 194 (8): 1415–24, discussion 1424–5. PMID 22046706.

{{navedi časopis}}: Vzdrževanje CS1: samodejni prevod datuma (povezava) - ↑ Albert, edited by Neil S. Skolnik ; associate editor, Ross H. (2008). Essential infectious disease topics for primary care. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. str. 66. ISBN 978-1-58829-520-0.

{{navedi knjigo}}:|first=ima generično ime (pomoč) - ↑ World Health Organization. »Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC)«. Diarrhoeal Diseases. Pridobljeno 3. maja 2012.

- ↑ World Health Organization. »Shigellosis«. Diarrhoeal Diseases. Pridobljeno 3. maja 2012.

- ↑ Weese, JS (Marec 2011). »Bacterial enteritis in dogs and cats: diagnosis, therapy, and zoonotic potential«. The Veterinary clinics of North America. Small animal practice. 41 (2): 287–309. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2010.12.005. PMID 21486637.

- ↑ Rousseaux, Wanda Haschek, Matthew Wallig, Colin (2009). Fundamentals of toxicologic pathology (2nd izd.). London: Academic. str. 182. ISBN 9780123704696.

- ↑ MacLachlan, edited by N. James; Dubovi, Edward J. (2009). Fenner's veterinary virology (4th izd.). Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic Press. str. 399. ISBN 9780123751584.

{{navedi knjigo}}:|first=ima generično ime (pomoč) - ↑ Fox, James G.; in sod., ur. (2002). Laboratory animal medicine (2nd izd.). Amsterdam: Academic Press. str. 649. ISBN 9780122639517.

{{navedi knjigo}}: Izrecna uporaba in sod. v:|editor2=(pomoč) - ↑ Zimmerman, Jeffrey; Karriker, Locke; Ramirez, Alejandro (15. maj 2012). Diseases of Swine (10th izd.). Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. str. 504. ISBN 978-0-8138-2267-9.

{{navedi knjigo}}: Prezrt neznani parameter|coauthors=(predlagano je|author=) (pomoč)

- Notes

- Dolin, [edited by] Gerald L. Mandell, John E. Bennett, Raphael (2010). Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases (7th izd.). Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 0-443-06839-9.

{{navedi knjigo}}:|first=ima generično ime (pomoč)

Zunanje povezave

- Gastroenteritis na Open Directory Project

- Diarrhoea and Vomiting Caused by Gastroenteritis: Diagnosis, Assessment and Management in Children Younger than 5 Years - NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 84.